TALK ABOUT PAIN

A Tribute to Marlon Brando

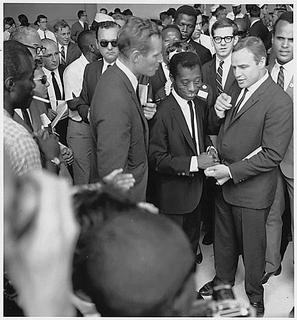

Civil Rights March on Washington, 1963

Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records

Marlon Brando's death at age 80 wasn't his first death, or his best.

His first death was a hanging, acted out on a school stage; the horrified audience thought it was real. His best death might have been in Last Tango in Paris, when, gut-shot by his nameless lover, he staggered backwards to a balcony but managed to stick his chewing gum under a rail before he collapsed. (That was Brando - the bit of business more eloquent than any speech.) There was nothing so inventive about his real demise. It was an ordinary death. No demons were reported to fly out of him.

The man who was arguably the best actor in the world left several ex-wives and sexual partners beyond count. He left at least nine children, and perhaps many more. He left behind a string of islands in the South Seas of Tahiti, and a fortressed house overlooking Los Angeles. He left behind 40 films, four of which appear on the American Film Institute's list of best films of the last century - A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. He left several generations of brooders and loners, from Jack Nicholson to Sean Penn, Paul Newman to Harrison Ford, Al Pacino to Russell Crowe, smoldering in his wake.

Already mourned for selling out his talent, discounting his art, squandering his time and money on lost causes, disappointing friends, co-stars, directors, studios, and fans, bloating his body, and failing his family, now Brando will simply be mourned. He's not expected to be forgotten.

***

No matter what he did during his long, perverse life, nothing can obliterate those early pictures of his beauty. He had a poet's face with hooded eyes and full lips over a brute's muscled arms and chest, and a gift for exploiting that body to express character. In the original 1947 production of "A Streetcar Named Desire," he used a languorous tiger's walk to stalk the stage as Stanley Kowalski, one of those tough guys who holds a cup of coffee, in Brando's words, "like an animal with a paw around it." Dressed in tight blue jeans and ripped T-shirt, exuding sexual menace, the 23-year-old Brando slurred and scratched himself opposite Jessica Tandy, an old-fashioned thespian -- a new kind of actor, wearing a new kind of costume, exhibiting a new kind of masculinity. At his opening night curtain call on Broadway, the audience cheered for half an hour.

By age 30, he'd conquered Hollywood as well, with a richly deserved Academy Award for his role as a corrupted ex-fighter who "coulda been a contender" in Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront. The lessons he'd learned from Stella Adler, the great Method acting teacher, were abundantly evident. He wasn't so much performing as he was inhabiting characters, losing himself in roles. He could emulate the wonderful British stage actors and perform Shakespeare's "Friends, Romans, countrymen" speech as Marc Antony in Julius Caesar. He could also create inarticulate brutes with such accuracy that audiences assumed he was playing himself. (In fact, he loved to read philosophy and could sit around discussing it for hours.)

The part of the sullen leader of a motorcycle gang in The Wild One, released months before On the Waterfront, gave Brando his enduring influence. "Hey, Johnny, what are you rebelling against?" his character was asked. "I dunno," Johnny said. "Whaddya got?" The movie is dated now, and Brando always disparaged it, but in the mid-'50s, it created a sensation. Brando's beatnik/biker brought style and attitude to a generation that began to dress like him, mutter like him, and swagger like him. James Dean, wearing "my last year's clothes and last year's talent," mimicked him in East of Eden, in the role Brando had rejected.

Though he had always been embarrassed about acting - just like "slicing baloney ... (only) the pay is better" - he didn't turn bitter about the profession until he found himself trapped in the role of Napoleon in Desiree, a "superficial and dismal" film and the first in a long string of disappointments. Notable among his misfires was Guys and Dolls, in which, through a trick of editing, Brando sang "Luck Be a Lady" - to Frank Sinatra, no less - though, as he put it, "I can't sing any better than a kangaroo." Paramount took away One-Eyed Jacks, which he had been directing for his own production company with excruciating care, then cut it and grafted on a new happier ending, an act of artistic sabotage that sent him into a severe depression. His three-hour version of the western was destroyed by the studio. "Any pretension I've sometimes had of being artistic is now just a long, chilly hope," he said.

He turned down Lawrence of Arabia to sign on as Fletcher Christian in MGM's colossal remake of Mutiny on the Bounty. Why spend two years in the desert, when he could work in Tahiti, a place he'd fantasized about since childhood? His portrayal of Christian as a supercilious gentleman was a surprisingly original one, but it couldn't make up for the lack of script or direction. Brando gleefully squandered the studio's time and money on location, and though he was only one element in the disaster, he was blamed for the failure of a picture that almost destroyed MGM. "I had learned long ago that once filming starts, the actor has the edge; too much money has been spent to abandon the project," he once admitted. "If he knows what to do, the actor can get away with almost anything." Brando gained 40 pounds during the filming and became a convert to the sensual Tahitian life; he began a long relationship with Tarita, his Polynesian costar with whom he had two children. Eventually he bought a nearby string of islands that became his haven from Hollywood.

Brando won back the regard of the film establishment and audiences in the early '70s with his beautifully underplayed portrayal of The Godfather for director Francis Ford Coppola. Jowly and steely-eyed, stroking a cat while he considered exercising his vicious power, he muttered, "Make him an offer he can't refuse," and a new generation experienced the Brando mystique. He followed that movie with a searing and sexual performance in Last Tango in Paris, but spurned the regard the two roles brought him. He had contempt for the fame that came from acting. He dodged personal questions from interviewers to lecture them about the history of the white man's treatment of Native Americans. He had stood behind Martin Luther King Jr. during the delivery of "I have a dream." He'd supported the Black Panthers in their early days, and he'd worked on a film for UNICEF about famine in India. These things mattered, not his celebrity. When he won an Academy Award for The Godfather, he sent a young actress in deerskin and feathers to reject the honor and make a speech for him on behalf of Native Americans. Not every man can enrage almost two billion people, but Brando managed. "He knew how to burn a bridge pretty good," Sean Penn observed.

He continued to work around his failing health until late in his 70s, doing charming work in The Freshman, mocking his Godfather role, and Don Juan Demarco. His last role was that of a hugely fat, gay, chatty swindler in The Score, as far from the sulky hunks of his youth as one could get.

~~~~

Such tortured talent had come, not from an inner city or an isolated backwoods, but from a middle-class home in Omaha, Neb. Brando's mother was an actress, though he never mentions this fact in his 1994 autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me. "She preferred getting drunk to caring for us," he wrote. His father was famously unfaithful, also a drunk and prone to vicious displays of temper. A salesman, he belittled his son for his choice of career, and always regretted having given his child his name. Brando embodied their contradictions: he was a sensitive actor; and he was also a bully who mocked such sensitivity -- and so full of rage, he once confided to a friend, he was afraid he'd kill someone.

He despised his father, yet hired him as his business manager. His father proceeded to lose the actor's fortune investing in cattle ranches and abandoned gold mines. Brando was indifferent to money, and gave most of it away, until, he claims, his alimony and child support payments became oppressive. Then he demanded millions to film cameos, most infamously, the father in Superman and the massive madman at the end of the journey in Apocalypse Now. But he also gave an Emmy-winning turn in Roots: the Next Generations for a token, and made his brilliant Oscar-nominated cameo in A Dry White Season for nothing.

He paid only $200,000 for his Tahitian atoll, and then poured money into it, developing projects that either never came to fruition or were swept away by typhoons. After his son Christian murdered his daughter Cheyenne's lover in 1990, and Cheyenne hanged herself five years later on Tetiaroa, Brando all but abandoned his retreat. He wept on the witness stand at Christian's sentencing, blaming himself.

"Marlon, oh, man," said his friend, the actress Maureen Stapleton, "you want to talk about pain --...." He had battled Anna Kashfi, his wife for less than a year, for 12 years for custody of Christian. He had his second wife, Movita, evicted. Lover Rita Moreno attempted suicide in his home. "There have been many (women) in my life, though I hardly ever spent more than a couple of minutes with any of them," he wrote with vast emotional distance.

Stories of his boorishness, his pranks, and his pugnacity abound, from throwing lighted firecrackers into a theater audience as a teenager to mooning sets as an aging star. "I put on an act sometimes and people think I'm insensitive," he once said. "Really, it's like a kind of armor because I'm too sensitive." He was a tuning fork that frequently vibrated out of control. He would deck people who put their hands on his shoulder; he couldn't bear to be surprised by a touch. "If there are 200 people in a room and one of them doesn't like me, I've got to get out." He couldn't hold a conversation with more than one person at a time. "If I heard anyone quarreling," he wrote, "I felt as if I were being consumed by insects. I couldn't stand loud voices or loud noises. Even the slamming of a door sent me into a panic."

Was the source of all that pain his mother's absence or his father's scorn? Maybe it came at the hands of his first love, his nanny Ermi. For five years, from the age of two to seven, she belonged to him. When he was seven, Ermi told him she was going away but would soon be back. He pined for weeks, until he realized she had betrayed him; she was never coming back. "From that day forward, I became estranged from this world," he wrote with stony finality. He lived 73 more years, a hurt child until the end.

_______________

©Marilyn Johnson, 2004.